Vince Cable, as business secretary in 2013, complained that the Bank of England was acting like a “capital Taliban”. This did not go down well with Bank officials.

The dispute was about how much capital the commercial banks should be required to raise. The banks, backed by Sir Vince, maintained that they were being asked to do too much. They couldn’t simultaneously raise capital and lend more to business.

It was special pleading and the Bank had every justification to reject it. Apart from being in poor taste to liken public servants to theocratic fanatics, it was also an error. Andrew Bailey, the Bank’s deputy governor responsible for prudential regulation, has been tough on the need to raise capital on the grounds that better-capitalised banks are better able to lend. And he’s right.

Banks are different from other companies. If a carmaker or an airline fails, the shareholders and employees take the hit, but the rest of the economy carries on. If a bank runs into trouble, its capital vanishes. And because the banks are tied together in the wholesale lending market, there’s an inherent risk that credit will seize up as they stop lending to each other. When that happens, the real economy crashes, as happened in 2008-09.

Banks have wider responsibilities than to their shareholders alone. Above all, they have a responsibility to ensure that the financial system is secure. Regulators need to keep constant pressure on them and must refuse to accept complaints that they’re being unfairly untargeted. That’s the lesson of the past few years.

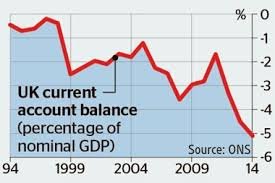

It’s taken a long time, but the financial crisis is over. In its report on stress-testing the UK banking system, published this week, the Bank of England concludes that the banks are sufficiently well capitalised to support the economy in the event of a global crisis. None of the seven biggest lenders needs to raise fresh capital. Separately, in its financial stability report, the Bank is sanguine about the external financial position of the British economy. Even though the current account deficit is wide by historical standards (reaching 5 per cent of GDP), it doesn’t see a risk to the capital flows financing it.

The regulatory system is stronger now. Under the one established by Gordon Brown, banking supervision was hived off to a new institution, the Financial Services Authority, which was asleep on the job. It presided over the first run on a British bank (Northern Rock) for more than a century.

Yet we know from the financial crisis that confidence can vanish rapidly and that markets tend to be swayed by waves of fear (or optimism), with huge economic damage. I used to argue that financial regulation should be counter-cyclical: in a business expansion we need more of it and in a downturn (when the first requirements is to get credit flowing again) we need less of it. I was wrong. The proper way of looking at the banking system is that it is always at risk of collapsing.

That’s the nature of its business model. Banks borrow short-term, on the wholesale markets, and lend long-term (Northern Rock got about 70 per cent of its funding from the wholesale market and repackaged it in the form of high-risk mortgage loans). The difference between the rates a bank pays and the rates it charges is its profit. Because government will step in to rescue banks if they fail, there is an incentive for them to take on too much risk in the search for higher returns.

Policymakers believed that competition between banks was an adequate way of serving the consumer. It was a disastrous error. For the economy to thrive, the banks need hands-on, intrusive regulation, harsher stress tests and hardnosed regulators to implement them.

Get At Me: